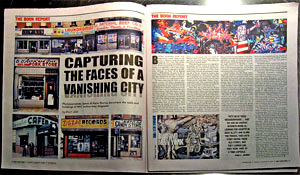

CAPTURING THE FACES OF A VANISHING CITY

Photojournalists James & Karla Murray document the walls and buildings of NYC before they disappear By Billy Jam

Before Burning New York appeared last month—James T. and Karla L. Murray’s brand new book capturing New York City current graffiti art—much of its subject matter had already disappeared. Even the book’s vibrant cover depicting a wall by Doze Green (one of over 300 artists featured in the full-color, 200-page art book) off of Bedford Avenie in Williamsburg was gone. It, like so many of the book’s other pieces of street art, had been displaced in the name of development in a city that is in a rapid upscale flux. “So many pieces from the book are gone already ... It says a lot about a changing New York,” says Karla. She and her photojournalist collaborator/husband James, who have for the past decade been tirelessly taking photos on the streets of New York, have witnessed the city’s changes firsthand. Most of the street art in their first book, Broken Windows, which captured New York graffiti from 1996 to 2001, is long gone, but much more surprising is the fact that over half of the subjects of their appropriately titled next book, Counter/Culture: The Disappearing Face of New York City’s Storefronts are already gone—and the book won’t be out for several more months. “By the time the book comes out, the majority [of the storefronts] will have disappeared,” James somberly predicts. He points to a panoramic shot of a block of Bleecker Street near Sixth Avenue that was shot over the past six years. “Two-thirds of that block is already gone!” When the Murrays, driven by a passion to photograph graffiti, started shooting New York’s street art in the mid-’90s, they had no inclination of ever putting out a book, never mind a series of books documenting a vanishing side of the city. Almost by accident, they found themselves as photo-journal authors after wandering into a bookstore where the impressive layout of a skateboard book titled Dysfunctional (published Ginkgo Press), caught their eyes. They jotted down the Bay Area indie publisher’s address and mailed off some copies of their work the next day. Soon they had a book deal for Broken Windows—so titled “because of that whole ‘broken window’ theory and what was going on with Giuliani at the time,” explains Karla. The sequel, Burning New York, which documents NYC graffiti the following five years from 2001 up to 2005, inadvertently led to their book on mom and pop storefronts. “We’d be in these neighborhoods, especially in the Bronx and Brooklyn, that we had no earthly business being in, looking for graffiti in back alleys and along the tracks,” says Karla, laughing. “And then we’d start seeing these old stores, and they looked like they were part of a time capsule. So we started taking more and more pictures [of them], and when we could, we would take [photos of] the entire block because that’s what we are really interested in showing: a whole strip. Then we would go back a short time later to take more pictures, but we’d see that a Starbucks or Duane Reade had moved in and replaced the mom and pops.” Counter/Culture will offer sharp, engaging photos (all shot on film), including many wide-angle, fold-out, panoramic shots, complimented by interviews with the owners of the shops. Almost as much as the storefront photos, these interviews narrate the history of New York as seen through the eyes of a small business owner. Take, for example, Catherine Keyzer, the sixtysomething owner of Katy’s Candy Store located on Tompkins Avenue by Vernon Avenue in Bedford-Stuyvesant, Brooklyn, who told the authors: “My store is the last of the penny candy stores in New York. I still sell candy for a penny and I even sell C&C colas for 25 cents. I am known around here as the ‘Dinosaur of Tompkins’ because I’ve been open for so long. I was born and raised in this Bed-Sty neighborhood and I’ve seen a lot of changes. I was here when it was all Jewish and Italian and when it changed to Spanish and black. I’ve been through the dope, crack and everything else this neighborhood has thrown at me. I speak three languages: English, Spanish and Motherfucker. You’ve got to be tough to survive around here.” Predictably, Katy’s Candy Store’s days are numbered since her landlord wants to convert the building into luxury-type apartments and, when her lease expires in 2009, she’ll be forced to close after 40 years in business. Changing economics, coupled with increasing city bureaucracy, are the two main culprits in wiping out New York City’s mom and pops. Examples, said Karla, include the annual $1,500 tax that the city imposes on small stores for simply having a neon sign, as well as forcing some small businesses to conform to a changing neighborhood by redesigning their storefronts. “In the past month or two the city passed, or rather enforced, a health code that says you can’t hang meats in the window anymore without refrigeration,” says James, pointing to a photo of the storefront of E. Kurowycky & Son Meat Products on First Avenue near 7th Street. “And it is putting them out of business because their business is based on smell and sight; their business has declined 20 percent to 30 percent since that law was enforced.” In reference to a shot of the charming C. DiPalo Latteria on Grand and Mott Streets—in business since 1925—James explains that, “The Little Italy guys are getting pushed out because their whole business is built on people coming and double-parking and leaving.” “Italians don’t really live in Little Italy anymore,” Karla adds. “So they double park and run in and get their cheese or whatever. But now the city stands there all day long and tickets people for double parking. And all the parking lots that used to be there have been taken over by condos.” To James and Karla Murray, passionate observers and documenters, both New York’s disappearing storefronts and its disappearing graffiti art have a great deal in common. Their vibrancy reflects the soul of New York and their demise reflects a sad step in a changing city. “Look at that!” says James, putting his finger on a wide shot of a New York block of mom and pop storefronts. “Every one of these has a face to them. It’s like a person almost.” Soon all that will be left of those diverse faces will be what the duo have been able to capture in photographs before the city’s cleansed of its muck, its character—and its history.

Photojournalists James & Karla Murray document the walls and buildings of NYC before they disappear By Billy Jam

Before Burning New York appeared last month—James T. and Karla L. Murray’s brand new book capturing New York City current graffiti art—much of its subject matter had already disappeared. Even the book’s vibrant cover depicting a wall by Doze Green (one of over 300 artists featured in the full-color, 200-page art book) off of Bedford Avenie in Williamsburg was gone. It, like so many of the book’s other pieces of street art, had been displaced in the name of development in a city that is in a rapid upscale flux. “So many pieces from the book are gone already ... It says a lot about a changing New York,” says Karla. She and her photojournalist collaborator/husband James, who have for the past decade been tirelessly taking photos on the streets of New York, have witnessed the city’s changes firsthand. Most of the street art in their first book, Broken Windows, which captured New York graffiti from 1996 to 2001, is long gone, but much more surprising is the fact that over half of the subjects of their appropriately titled next book, Counter/Culture: The Disappearing Face of New York City’s Storefronts are already gone—and the book won’t be out for several more months. “By the time the book comes out, the majority [of the storefronts] will have disappeared,” James somberly predicts. He points to a panoramic shot of a block of Bleecker Street near Sixth Avenue that was shot over the past six years. “Two-thirds of that block is already gone!” When the Murrays, driven by a passion to photograph graffiti, started shooting New York’s street art in the mid-’90s, they had no inclination of ever putting out a book, never mind a series of books documenting a vanishing side of the city. Almost by accident, they found themselves as photo-journal authors after wandering into a bookstore where the impressive layout of a skateboard book titled Dysfunctional (published Ginkgo Press), caught their eyes. They jotted down the Bay Area indie publisher’s address and mailed off some copies of their work the next day. Soon they had a book deal for Broken Windows—so titled “because of that whole ‘broken window’ theory and what was going on with Giuliani at the time,” explains Karla. The sequel, Burning New York, which documents NYC graffiti the following five years from 2001 up to 2005, inadvertently led to their book on mom and pop storefronts. “We’d be in these neighborhoods, especially in the Bronx and Brooklyn, that we had no earthly business being in, looking for graffiti in back alleys and along the tracks,” says Karla, laughing. “And then we’d start seeing these old stores, and they looked like they were part of a time capsule. So we started taking more and more pictures [of them], and when we could, we would take [photos of] the entire block because that’s what we are really interested in showing: a whole strip. Then we would go back a short time later to take more pictures, but we’d see that a Starbucks or Duane Reade had moved in and replaced the mom and pops.” Counter/Culture will offer sharp, engaging photos (all shot on film), including many wide-angle, fold-out, panoramic shots, complimented by interviews with the owners of the shops. Almost as much as the storefront photos, these interviews narrate the history of New York as seen through the eyes of a small business owner. Take, for example, Catherine Keyzer, the sixtysomething owner of Katy’s Candy Store located on Tompkins Avenue by Vernon Avenue in Bedford-Stuyvesant, Brooklyn, who told the authors: “My store is the last of the penny candy stores in New York. I still sell candy for a penny and I even sell C&C colas for 25 cents. I am known around here as the ‘Dinosaur of Tompkins’ because I’ve been open for so long. I was born and raised in this Bed-Sty neighborhood and I’ve seen a lot of changes. I was here when it was all Jewish and Italian and when it changed to Spanish and black. I’ve been through the dope, crack and everything else this neighborhood has thrown at me. I speak three languages: English, Spanish and Motherfucker. You’ve got to be tough to survive around here.” Predictably, Katy’s Candy Store’s days are numbered since her landlord wants to convert the building into luxury-type apartments and, when her lease expires in 2009, she’ll be forced to close after 40 years in business. Changing economics, coupled with increasing city bureaucracy, are the two main culprits in wiping out New York City’s mom and pops. Examples, said Karla, include the annual $1,500 tax that the city imposes on small stores for simply having a neon sign, as well as forcing some small businesses to conform to a changing neighborhood by redesigning their storefronts. “In the past month or two the city passed, or rather enforced, a health code that says you can’t hang meats in the window anymore without refrigeration,” says James, pointing to a photo of the storefront of E. Kurowycky & Son Meat Products on First Avenue near 7th Street. “And it is putting them out of business because their business is based on smell and sight; their business has declined 20 percent to 30 percent since that law was enforced.” In reference to a shot of the charming C. DiPalo Latteria on Grand and Mott Streets—in business since 1925—James explains that, “The Little Italy guys are getting pushed out because their whole business is built on people coming and double-parking and leaving.” “Italians don’t really live in Little Italy anymore,” Karla adds. “So they double park and run in and get their cheese or whatever. But now the city stands there all day long and tickets people for double parking. And all the parking lots that used to be there have been taken over by condos.” To James and Karla Murray, passionate observers and documenters, both New York’s disappearing storefronts and its disappearing graffiti art have a great deal in common. Their vibrancy reflects the soul of New York and their demise reflects a sad step in a changing city. “Look at that!” says James, putting his finger on a wide shot of a New York block of mom and pop storefronts. “Every one of these has a face to them. It’s like a person almost.” Soon all that will be left of those diverse faces will be what the duo have been able to capture in photographs before the city’s cleansed of its muck, its character—and its history.